This article by Carol Smart first appeared in the pages of Kenilworth History back in 1995:

WARWICKSHIRE IN THE DARK AGES, SOME UNANSWERED QUESTIONS

by Carol Smart

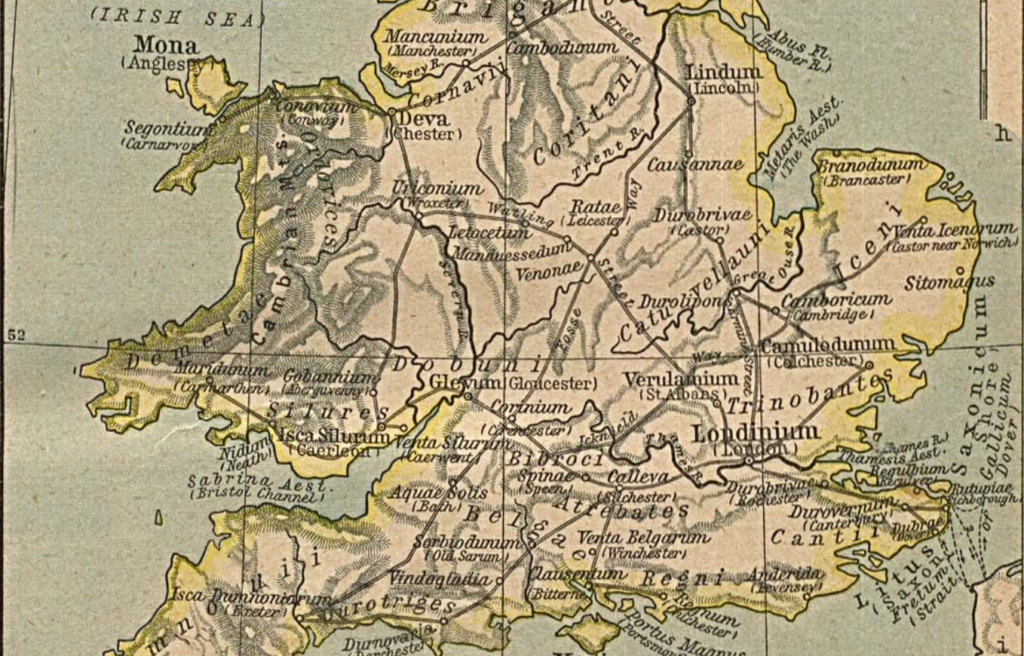

“The Dark Ages” is here taken to mean the fifth and sixth centuries, the period between the final collapse of Roman administration at the beginning of the fifth century and the dim emergence of Anglo-Saxon kingdoms in the seventh century. In relation to this period it must be admitted that “Warwickshire” is a completely arbitrary geographic unit (since the organisation of the country into shires only appears in the eleventh century), but it may serve as a useful microcosm of the whole.

The history of the period generally is hard to elucidate, and, unusually, there is no agreed consensus among historians; almost any statement made can be plausibly countered. Most of what was once believed to be incontrovertible by earlier historians is now likely to be seriously questioned. The paucity of written history of anything near to contemporary date, the unreliability of what little written evidence exists, plus the random nature of the archaeological evidence, limited as it is to chance discoveries, all combine to make the study of the period unusually tantalizing.

Although Alcester is not known to have had any administrative function, it must have been a sophisticated urban settlement, with stone-built houses with tiled roofs, decorated plaster on the walls, at least one with a hypocaust, as well as more modest timber-framed houses. It also had some local industries – a tannery is suggested – and elaborate town defences. A much more modest settlement is known at Tiddington, where there were virtually no stone buildings, plainly an agrarian rather than an urban settlement. Several other villages are known to have existed, from Coleshill in the north, through Baginton and Princethorpe, to Stretton-on-Fosse in the extreme south. In addition, there were a number of single farmsteads – it has been stated that fifteen villa sites are known in the Avon valley ¹. None of these is particularly grand – the term “villa” is often used to identify almost anything larger than a one-roomed house, and in the Warwickshire context the term “farmhouse” might be more appropriate. However, some of them have been found to be decidedly comfortable, like the courtyard villa at Radford Semele, with decorated wall plaster. Industrial sites are also known – the pottery at Wappenbury Wood and the tile factory at Kenilworth are examples.

A slightly separate group of settlements is known, running along or not far from, the two great highways of Watling Street and the Fosse Way: one of these is Chesterton, which originated as a fort. Mancetter also started as a fort, but developed into a substantial industrial complex, principally making pottery, with the adjacent area of Hartshill engaged in the same trade.

So, a hazy picture emerges of these towns, villages and farms, but the lives of the people who lived there are more shadowy It is reasonable to assume they spoke Celtic and Latin, but were they literate in Latin? Some of them must have been, in what was after all a literate society. Although very little evidence is known in Warwickshire, even a label on a jar of mackerel implies that prospective purchasers could read it. Some sections of society lived in considerable comfort – there is evidence for water supply, baths, heated rooms, painted walls, mosaic floors, good quality utensils.

An administration existed, and was efficient enough to build town defences, repair roads, collect taxes – the principal function of government, after all. There were markets for the products manufactured in Warwickshire, and the means to transport them – Hartshill pottery has been found in many parts of North Britain. It was possible to travel – some of the potters who worked in Hartshill moved on to set up potteries further north. Religious belief and practices cannot be determined, but Romano-Celtic temples are known in the area, at Coleshill and possibly Alcester. Nothing has been found in Warwickshire to suggest Christian influences, although there is a slight indication of Christian beliefs from Wall, just outside the Warwickshire boundary.

Now consider Warwickshire two centuries on, around 600. Possibly an Anglo-Saxon society was beginning to emerge – the people called the Hwicce first come to notice early in the seventh century. But there are virtually no coins, no pottery, no stone buildings – almost the only material evidence of these people is their weapons and their jewellery. So what happened in these two hidden centuries?

Historians formerly accepted the story of a large-scale invasion of groups of peoples from the area of North Germany, who killed or drove out the existing population, took over the land, and replaced Romano-British culture with their own. More recently writers have suggest that fairly small numbers of elite warrior bands arrived and supplanted a romanised land-owning class, perhaps of not dissimilar numbers; in this scenario the mass of the population remained, working the fields for new masters.

The sole near-contemporary literary source is Gildas – “The Ruin of Britain”, which was probably written in the first half of the sixth century (and in Latin, of course). The work is, in effect, a sermon written by a Christian cleric, calling for repentance by a number of sinful kings, and the account he gives of fifth century Britain is really incidental to this purpose. His story (which is the source for Bede’s later history) briefly, is that after the withdrawal of the last Roman soldiers from Britain, the British appealed to Rome for help, and were told to defend themselves, which they did with some success. Subsequently Saxon warriors were hired to help in the defence of Britain, but in due course rebelled and ravaged the country. A local leader, Ambrosius, took over the defence of the country, and successfully repelled the Saxons, defeating them at a battle called Badon, and thereafter, until Gildas’ own time the country was peaceful and prosperous.

All this is assumed to cover the period from about 410 to around the middle of the sixth century. Unhappily, the date of composition is not certain, nor is the place where Gildas was writing; frequently neither people nor places in the story are clearly identified, although it is plain that the kings he castigates were rulers of small kingdoms in Wales and Western Britain; and some of his statements are demonstrably false. Finally, nothing in the “The Ruin of Britain” can plausibly be related directly to Warwickshire. Since, however, it is the only near contemporary source it cannot be wholly disregarded. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle is much less contemporary, dating from the ninth century, and even less immediately relevant, since it concerns primarily the affairs of Wessex.

Looking more at Warwickshire itself, the archaeological evidence shows a slow decline of Romano-British society throughout the fourth century – the house in Glasshouse Wood, for instance is thought to have been abandoned early in the fourth century, and none of the other excavated farmhouses seems to have been in use beyond the fourth century. Coins of course virtually disappear by the fifth century – since coins were produced principally to pay the army, and the army had gone.

The small town of Alcester shows more signs of continuing into the fifth century, but this is far from certain. Pottery was still produced at Mancetter till late into the fourth century, but not beyond.

The archaeological evidence for Anglo-Saxon settlement in Warwickshire in the fifth century is very limited indeed, and not very prolific for the sixth century either. A cemetery at Wasperton revealed some fifth century Anglo-Saxon graves, and sixth century cemeteries have been found, some in the Avon valley, like Bidford-on-Avon and Tiddington, others toward the eastern side of the county, like Churchover or Off church. Simple sunken-floored wooden houses have been traced in a few places, for instance Baginton, but no trace has been found of more substantial buildings before the eighth century.

Can these scattered fragments of evidence clarify the history of the period in Warwickshire? One thing is quite plain, the Anglo-Saxons did not take over and inhabit, either peacefully or by force, the towns, villages and farmhouses of the Romano-British – they had all been abandoned. Only one of the excavated sites, Wasperton, has produced any evidence of continuity. At Alcester there is no further trace of habitation till late in Saxon times, indeed, rather surprisingly, it is not mentioned in Domesday. There are many instances of later settlements developing close to, but not precisely over, a British farmhouse or village; Kenilworth itself is an obvious example, as is Chesterton. Elsewhere the Anglo- Saxons may have inhabited basically the same site as their predecessors, but there is a substantial time-lag between the disappearance of the British and the appearance of the Anglo-Saxons; Baginton might be an example here. Only in one place, Wasperton, are there signs of British and Saxon living in the same community; here the cemetery has produced evidence of British and Saxon burial practices alongside each other, apparently contemporaneously, and dating to the fifth century.

None of this rules out the idea that an Anglo-Saxon elite supplanted a British elite – but chose not to live in substantial houses or towns – while a peasant class continued to work the land, their lives being invisible, archaeologically, in Saxon times just as they had been in Roman times. There is some support for this theory, from the fact that pollen records, where they are available, do not always suggest a major change in vegetation (as they should do if land had gone out of cultivation), and also from the analogy with the much better-documented history of the Norman invasion. None of the sites in Warwickshire shows any sign of a violent end to its existence. The possible survival of Warwickshire’s only town, Alcester, to a later date than any of the villas might be thought to suggest a removal, or flight, of landowners to the nearest defended town.

There are, however, some facts, and some probabilities, which throw doubt on this version of events. Two of the villa sites, one at Ashow and the one in Glasshouse Wood, have produced evidence of the preservation of the British field systems under woodland which grew up after their abandonment – now this does not really support the idea of a continuing peasant class remaining to work the land. It is also, surely, strange that these Avon valley farmhouses were abandoned during the fourth century – there is nothing to show that any of them continued into the fifth century. Why did the owners or tenants leave at this time? They were not then threatened by any invaders – even into the fifth century the evidence indicates only a very small Saxon presence in Warwickshire.

Should the collapse of romanised life then be attributed to other causes? The ending of towns, which were the focus of Roman civilisation, clearly points to a collapse of the administration. Even if Alcester had no administrative function it must still have been the natural centre for the Avon valley, and its collapse must have had wide repercussions.

However, even if the administration disintegrated early in the fifth century, Gildas makes it plain that small “kingdoms” appeared, and that they were Christian and literate. He seems to be talking about the most westerly parts of Britain, but this does not necessarily rule out successor states in the midlands too. Further, British states are known to have survived much later – Welsh kingdoms outlasted Anglo-Saxon rule in England. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle tells of three kings of Bath, Cirencester and Gloucester who combined to resist the Saxons and were defeated at the battle of Dyrham, near Bath, in 577.

Nothing is known about the extent of the territories of these three kings, but it is not impossible that the Avon valley came within the influence of either Gloucester or Cirencester. With administrative collapse came economic collapse.

Coinage from Warwickshire sites ceases after the fourth century; the extensive potteries of North-East Warwickshire also ended at about this time. A subsistence economy must have replaced the sophisticated Roman model.

The arrival of Anglo-Saxons, either as small elites or as a mass migration, seems to have been a very gradual process. The most natural way to reach the Avon valley would have been from the Severn, so it is unlikely that Saxons could have established themselves on the Avon before the crucial battle of Dyrham in 577; only one place in the Avon valley, Wasperton, suggests the presence of Saxons before that. It seems likely that sixth century settlement in the East of the area was by Angles coming over the watershed from rivers flowing into the North Sea.

It has been suggested that the people called the Hwicce, who inhabited Warwickshire in the seventh century before the rise of Mercia, were a fusion of Angles and Saxons.

So did these immigrants come to an empty land, full of ruins? Well, certainly full of ruins; an Old English poem of the eighth century says

“Splendid is this masonry – the fates destroyed it,

the strong buildings crashed, the work of giants moulders away,

the roofs have fallen, the towers are in ruins,

the barred gate is broken.”

Whether the land was sparsely populated by unresisting peasants is more problematic. The evidence of place names has been used to suggest that the invaders must have obliterated the native Britons. While it is obviously true that almost all Warwickshire settlement names derive from Anglo-Saxon, this is not really as conclusive as it seems. Most local river names are British in origin, which implies that the Saxons learnt them from local British people.

Further, the great majority of Saxon names refer to places which were not in existence previously – a new name was inevitable because there could not have been an old name.

But the matter of language is surely more conclusive; we speak English, not a version of Celtic like Welsh, nor a language closely related to Latin like French.

Is it really possible that a numerically small ruling class could have imposed their language and culture on a large indigenous population, and all in the space of a century or so? The Norman invaders could not do it, could the Saxons?

So, were the romanised Britons wiped out, or expelled – an early example of “ethnic cleansing”? Gildas rather suggests this. But there are two other possible factors. The population may have been reduced and weakened by disease – Gildas talks of the Britons being afflicted by plagues (as a punishment for sin, in his eyes). It is easy to forget how devastating epidemic disease could be in earlier times: we know that the Black Death reduced the population sufficiently to wipe out villages, in Warwickshire as in other counties. Even more recently the ’flu epidemic of 1918 killed 20 million people worldwide (compared to the 81⁄2 million soldiers killed in World War I). All the Warwickshire evidence suggest the abandonment of farmhouses in the fourth century; one can speculate that a greatly reduced workforce made it impossible to continue working the land.

A further speculative factor is a change in climate. Climatological studies do suggest a cooling of the earth’s climate around the late Roman period, and a fairly simple agriculture would be susceptible to even a slight change in rainfall or temperature. There is some evidence to support this; excavations at Flag Fen, near Peterborough, have shown that the site, in use since the Bronze age, was abandoned in late Roman times due to fresh-water flooding. In Warwickshire itself it has been suggested that the Avon valley became wetter at this time and more prone to flooding ² Study of pollen from Alcester also confirms an increase in wetland plants at this period.

The Romano-British of Warwickshire were unable to maintain their civilisation – that at least is certain. Does it make sense, in human terms, to imagine a people demoralised by social collapse, numerically reduced by epidemic disease, weakened by a series of bad harvests, and therefore unresisting in the face of a few vigorous incomers?

References

¹ Hook, D, Anglo-Saxon Landscape; The Kingdom of Hwicce. 1985.

² Slater, TR. & Jarvis eds Field and Forest: An Historical Geography of Warwickshire and Worcestershire. 1982.